North Pennines Stargazing Week

Chasing the Northern Lights

5 December 2024

Chasing the Northern Lights

– the what, why, when, and the “has anybody got any spare gloves?”, of aurora hunting

by Dr Martin Kitching

‘What power disbands the Northern Lights

After their steely play?

The lonely watcher feels an awe

Of Nature’s sway,

As when appearing,

He marked their flashed uprearing

In the cold gloom–

Retreatings and advancings…’

extract from ‘Aurora Borealis’ by Herman Melville (1819-1891)

Melville is one of many authors and artists through the ages to take inspiration from the Northern Lights, but what is this natural phenomenon that was adopted by an author, probably best known for his epic tale of a grudge-bearing ship’s captain (it was only half a leg, after all – surely the joy that whales bring to the world more than compensated for that…), as an allegory for the end of the American Civil War?

It’s a cold September night, just after the autumn equinox. The Milky Way is a bright band across the sky overhead, with the majestic Summer Triangle of Deneb, Vega and Altair, and in a layby in the North Pennines, shadowy figures are gathered like a coven welcoming the dark night. Murmuring and muttering can be heard as faces are briefly illuminated by the light of the LCD screen on the back of a camera “Have you got her yet”? “I’m not sure, maybe. What do you think?” “Could be. Looks like faint green?”. They may walk among us in the spotlight of daytime as our friends, relatives and neighbours, but by night they become the aurora hunters; in search of the Green Lady, Nimble Men, Mirrie Dancers…

In its simplest terms, the aurora is created when enhanced solar wind (from coronal mass ejections or coronal holes) interacts with the Earth’s magnetic field. If the interaction disturbs the magnetic field sufficiently then the high energy particles in the solar wind are accelerated along the magnetic field lines and interact with oxygen and nitrogen in the atmosphere. Adding excess energy to the atoms or molecules of oxygen and nitrogen raises them to an ‘excited’ state, from which they release their excess energy as light – the visible Aurora Borealis/Northern Lights (Aurora Australis/Southern Lights in the southern hemisphere).

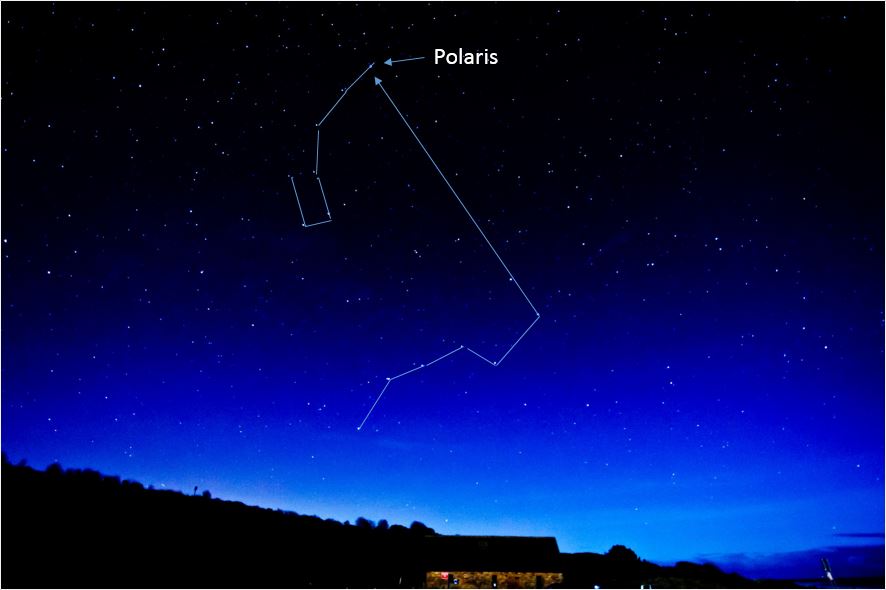

Our eyes are more sensitive to green than to other colours, so that’s the colour most frequently seen, although as far south as the North Pennines AONB, the aurora is unlikely to have any visible colour, and will usually be a silvery grey. It would also need to be a particularly impressive display to have any structure beyond a faint arc on the northern horizon, with maybe rays or pillars of light stretching up from it. The very human failings of our eyes in low light don’t affect camera sensors though, which is why most photographs of the aurora are colourful and show structure that our eyes can’t see. A camera on which you can set the exposure time to be up to ~30s and a good sturdy tripod are an important part of your quest to try and capture an image, even if your eyes are telling you there’s nothing visible. Make sure you know where north is – easily determined if you can see The Plough, because that’s the direction you need your camera to be pointing.

I’d recommend determining your camera’s best settings for photographing the night sky, without getting any obvious star-trailing (search for ‘500 rule’ but remember that rules aren’t set in stone) or too much ‘noise’ (increase your ISO setting until you find the highest setting that still produces images you’re happy with) and an aperture that’s around the second smallest number you can choose for your lens, and use that as your initial exposure for the aurora too. If you get a really bright aurora you can always reduce exposure time and possibly capture structure rather than just a fuzzy arc. I took this image at Cresswell, on the Northumberland Coast, in March 2016 and I was eventually using an exposure time of 6 seconds (having started at 20s).

It probably goes without saying, but you really need a sky that’s as free from artificial light pollution as possible. The North Pennines is an area that’s blessed in that regard, with the density of Dark Sky Discovery sites being a testament to that. A low northern horizon is always helpful too, so that may mean getting somewhere quite high, to compensate for the higher ground to the north of the Tyne gap. The horizon being cloud-free is the next part of the jigsaw. Once everything’s in place, and you’ve made sure you’re warm and safe in your chosen location, you only need one more thing, and that’s the aurora itself (or herself!)…

There are a lot of dice rolling that all need to fall the right way up for a good aurora display and some of them don’t stop rolling until very late in the game, which makes the aurora unpredictable (although more frequent in the few weeks either side of the spring and autumn equinoxes) but you can equip yourself to be prepared for when it does happen. Spaceweather.com will show you if there are Earth-facing coronal holes or sunspots on the Sun and if there’s been a coronal mass ejection then the enhanced solar wind could arrive 2-4 days after that. Most aurora forecast apps are notoriously unreliable but the Glendale app https://aurora-alerts.uk/ uses real-time data so is almost always accurate, and the ‘AUK – Aurora UK’ Facebook group is a great source of information and updates.

Good luck!

Martin is a Director of Northern Experience Wildlife Tours and Astroventures; wildlife guide, photographer, astronomer, poet, and deeply in love with the sea and the sky – preferably turbulent and awe-inspiring, and dark and cloudless, respectively. He’s immensely grateful for his awesome friend Laura and her knowledge and understanding of the aurora, and infectious enthusiasm for chasing the northern lights, which continues to inspire him to learn, search, and gaze at the sky.

If you have any questions he can be contacted at martin@newtltd.co.uk