News

Curlews Calling

5 December 2024

Curlews Calling with Christina Taylor

Christina Taylor, from the RSPB and Curlew LIFE Project Officer (Northumberland and Cumbria), presented a webinar on curlew ecology, distribution, trends, and habitat in April which was followed by a curlew ‘drawalong‘ with Fellfoot Forward artist Alex Jacob-Whitworth.

Christina summarised the aims and objectives of the Curlew LIFE Project and the importance and relevance of the Fellfoot Forward area for curlew conservation.

Waders

Global travellers which come in all shapes and sizes, waders can be found in a variety of habitats, dependent on the species and the time of the year, including rivers, lakes, shore, tundra, woodland, steppe, grassland, and dry, rocky areas.

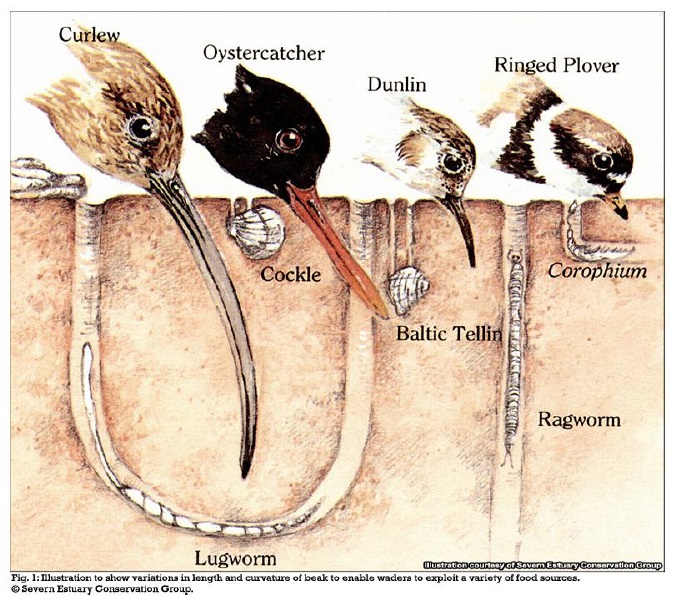

A large part of a wading bird’s diet is made up from aquatic organisms – from worms hiding in the mud to molluscs and crustaceans hiding under rocks. All wading birds possess long legs that enable them to stay clear of the water while they look for food. The clue to what waders eat and how they do it is is in the beak. Most waders are specially adapted to finding a certain prey species just under the surface of a wetland. Waders with longer bills, like curlew and snipe, use them like chopsticks to scoop up worms deeper in the mud, whilst the shorter beaked lapwings use theirs to catch aquatic insects just under or on the surface.

Eurasian Curlew

Numenius arquata. The largest European wading bird and spends much of the year on coasts or estuaries. It has a very long, curved bill and long dark grey legs, is well camouflaged and in flight has a white wedge on its back.

Curlews are long lived, on average 11 years but the record is 32 years. They are generally faithful to each other and return to the same place every year to breed, from the age of 2. The measure, on average, 50-60cm in length, with a wingspan of 80-100cm, and weigh between 575-1000g (females averaging 1000g and males averaging 770g). The main visible difference between the sexes is that the female has a longer bill, but the female is also larger than the male. Juveniles have much shorter bills.

Curlews migrate north and inland to breed on moorland or grassland with the first curlews of spring heard in the uplands in February. The first nests are made in April and most nests have an egg by the beginning of May, but a failed attempt to raise a brood may result in a second, later attempt. The nest is a shallow cup formed in grass that is 20-30cm high so that they can hide from predators, but put their heads above the grass to see what is going on. A curlew usually lays up to four eggs, but fewer eggs may be laid, particularly if birds are older or the nest is a second attempt replacing an earlier loss. Both male and female birds take turns to sit on the nest before eggs hatch. Eggs are incubated for 27-29 days.

From hatching to fledging the period is about 32–38 days. If a nest fails because the chicks are lost a pair of curlews will not make a second attempt to nest.

Curlew like rough damp pasture, hay meadows, hill allotments, bracken stands, and heather, where there is tussocky vegetation to forage and feed in. Adults use their distinctive long bills to probe the ground for worms, caterpillars and invertebrates. Curlew are unlikely to successfully nest in heavily stocked fields. They nest on flat ground, drier than the ground that they forage in, and usually away from tall trees and shrubs that harbour predators. Invertebrate rich grassland provides safe ground for chicks to feed in. They prefer a range of sward heights to provide shelter and hiding places from predators, but not so dense that the grassland is difficult for a chick to move through.

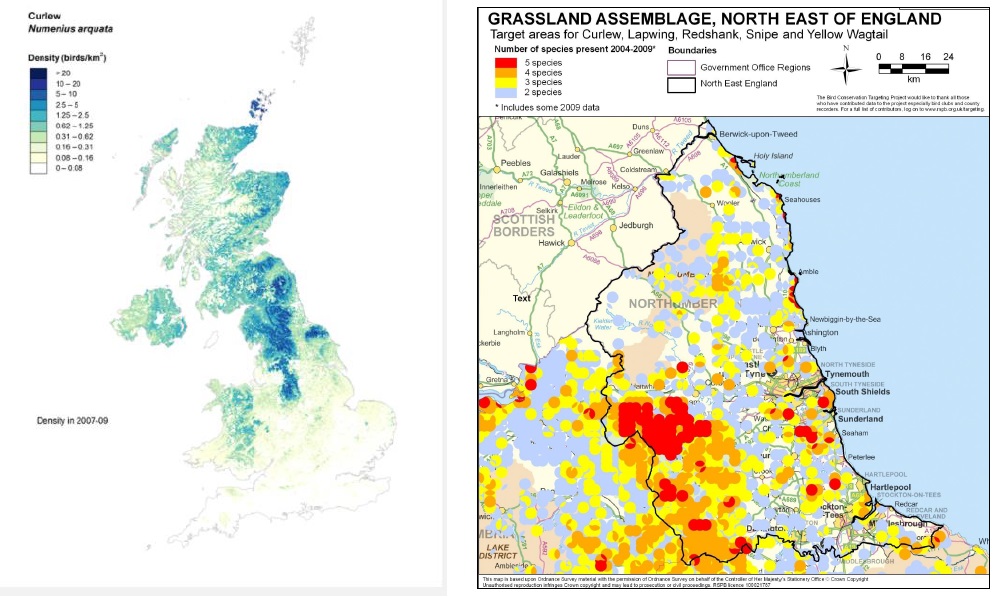

Curlew are in crisis with 68,000 breeding pairs in the UK, mainly in the Northern Uplands, about 25% of the global Eurasian Curlew population. There has been a 31% decline in England since 1995 (48% in the UK), and Curlew is listed as vulnerable to extinction in Europe, and globally, is considered near threatened (IUCN Red list).

The evidence to date suggests declines are largely due to the loss of breeding grounds as a result of policy driven, large-scale changes in land use, including agricultural intensification, woodland planting, predation, disturbance, and climate change. Studies have found that, in most cases, breeding pairs are failing to raise enough young to maintain stable populations, currently 0.5 chicks per pair per annum.

Curlews in Crisis

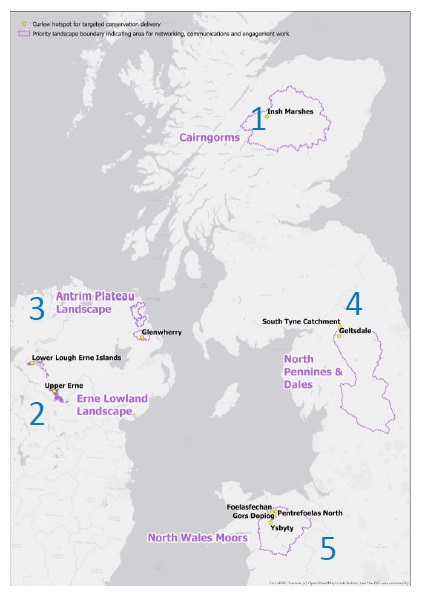

Curlew LIFE aims to deliver concrete action to halt the decline of curlew within five priority landscapes across the UK. In addition, it will define and catalyse future action to maintain viable populations of curlew within these landscapes and halt the decline at the national level. Effort will be greatest in Wales and Northern Ireland but there will also be work at key sites in Scotland and England, to create ‘centres of excellence for curlew conservation’ to inform wider work in the future.

The project started on 1st October 2020 and will run until 31st December 2024 with funding of £3.68 million and £1.47 million match funding. The Curlew LIFE Project areas are:

1. Insh Marshes, Cairngorms, Scotland

2. Erne Lowlands, Northern Ireland

3. Glenwherry , Antrim Plateau, Northern Ireland

4. Geltsdale /Hadrian’s Wall Corridor, England

5. Conwy (4 sites), Wales

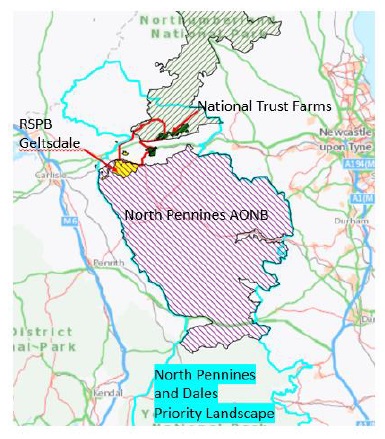

The Geltsdale and Hadrian’s Wall corridor is 15,000 hectares with 220 breeding pairs of curlew. The Curlew LIFE project will include a monitoring programme with the aim of identifying areas that would benefit from conservation actions and to evaluate responses to conservation actions by monitoring:

• habitat condition

• predator abundance

• curlew abundance

• breeding success

Curlew LIFE will also:

- Work with North Pennines AONB, Northumberland National Park and National Trust and the farming community – habitat improvements

- Demonstration sites including RSPB Geltsdale Reserve – demonstrate curlew conservation techniques.

- Events, training, workshops

- Build support for curlew

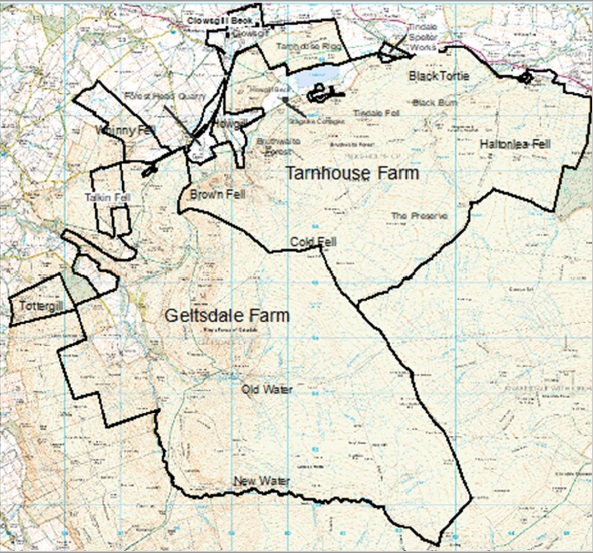

Geltsdale Nature Reserve is 5,500 hectares, consisting of Tarnhouse Farm (RSPB) and Geltsdale Farm (Weir Trust). It ranges from 200m to 620m at Cold Fell and has a mosaic of upland habitats including blanket bog, heath, wet grassland, meadows, and woodland.

How can you help?

Farmers and land managers can help in a number of ways and information is available on the Northern Upland Chain website.

Grazing Management

• Mixed stocking

• Hardy cattle breeds will eat rushes and coarse vegetation

• Cattle create a “bumpy” sward with hoof marks

• Lower stocking rates during spring

• Grazing just with sheep can create a very uniform sward

• Diverse swards will benefit all wader species

Rushes and waders

Rushes are an important element of wader breeding habitats, but … given the right conditions, soft rush can quickly dominate grassland! Ongoing management may be necessary to prevent fields becoming unsuitable for breeding waders.

Creating scrapes

• Raises water table in a localised way

• Increases invertebrate biomass

• Provides chick feeding habitat

• Provides muddy edge for adults

High Nature Value Farming

Low intensity farming systems, which are economically marginal and often undervalued, are also:

• valuable for wildlife and the natural environment

• offer public benefits

Volunteer

Report your sightings

On the Northern Upland Chain Local Nature Partnership website.

Spread the word

Use these hashtags on social media:

#CurlewLIFE

#WorldCurlewDay

#Curlew

#Curlewcrisis

#watchyourstep

Watch your step

Watch the RSPB’s video here. Stay on the path and keep your dog on the lead during nesting season to avoid disturbing ground nesting birds.